The fern fossils from St. Clair, Pennsylvania are world famous. These plant fossils occur in black shale matrix, and have a characteristic white coating of the mineral pyrophyllite. These fossils are about 300 million years old, dating from the Pennsylvanian Epoch of the Carboniferous Period, when the great anthracite (aka, hard coal) deposits formed in the Alleghany Mountains. The fossil plants are associated with the coal beds, since coal is the product of thick accumulation of decayed and compacted plant material.

The town of St. Clair, Pennsylvania

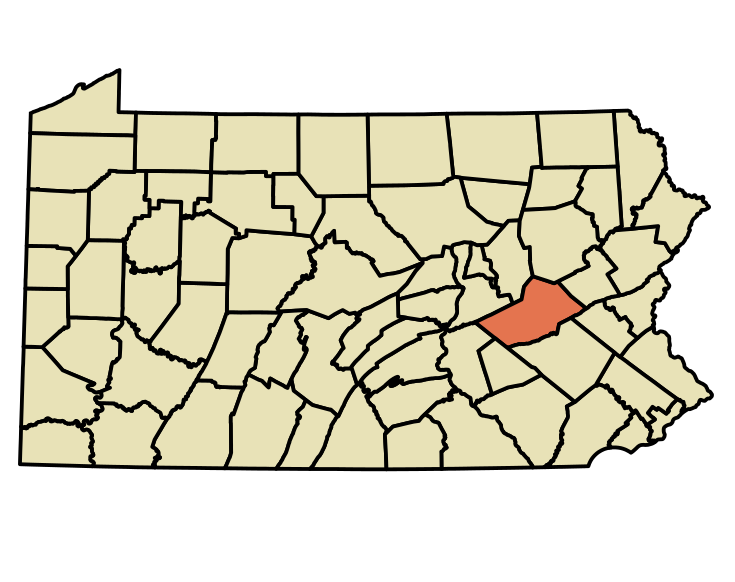

The borough of St. Clair was established in 1850, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is located in Schuylkill County, in the Southern Coal Region, just two miles from Pottsville, the county seat. Today, St. Clair has just over 3,200 residents.

Map of Pennsylvania and Schuylkill County

St. Clair is my husband’s hometown. He was born and raised there, the oldest of five siblings. His father was a coal miner who worked almost his entire life – from the age of 11 - in the underground anthracite coal mines, until they closed in the early 1950s. He, like so many other coal miners, died from black lung in his mid-70s.

My husband, Andy Herman, left St. Clair after graduating high school at 17, and has only returned to visit family. Andy had a wonderful collection of local minerals and fossils that he had assembled during his childhood, but while he was away serving in the US Army, his parents got a 30-day notice from the mine company to vacate their home, as the surface area was being stripped by the big shovel for the underlying coal. The entire collection vanished.

When I first visited St. Clair in the mid 1990s, primed with my husband’s description of the area’s devastation and images from movies about desolation around the coal mines, I was surprised to see the surrounding hills (many of which were tailing piles from the mines) had been mostly reclaimed by trees and vegetation. However, a closer look showed that the ground under the trees was covered with black coal residue. Andy remembers the black coal scum that used to flow in the Mill Creek, which runs through the center of St. Clair. Now, it has mostly been cleaned up.

This beautiful, large St. Clair fern fossil specimen in our collection is 2 feet, 5 inches wide and 17 inches tall, with visible fossils on the both sides.

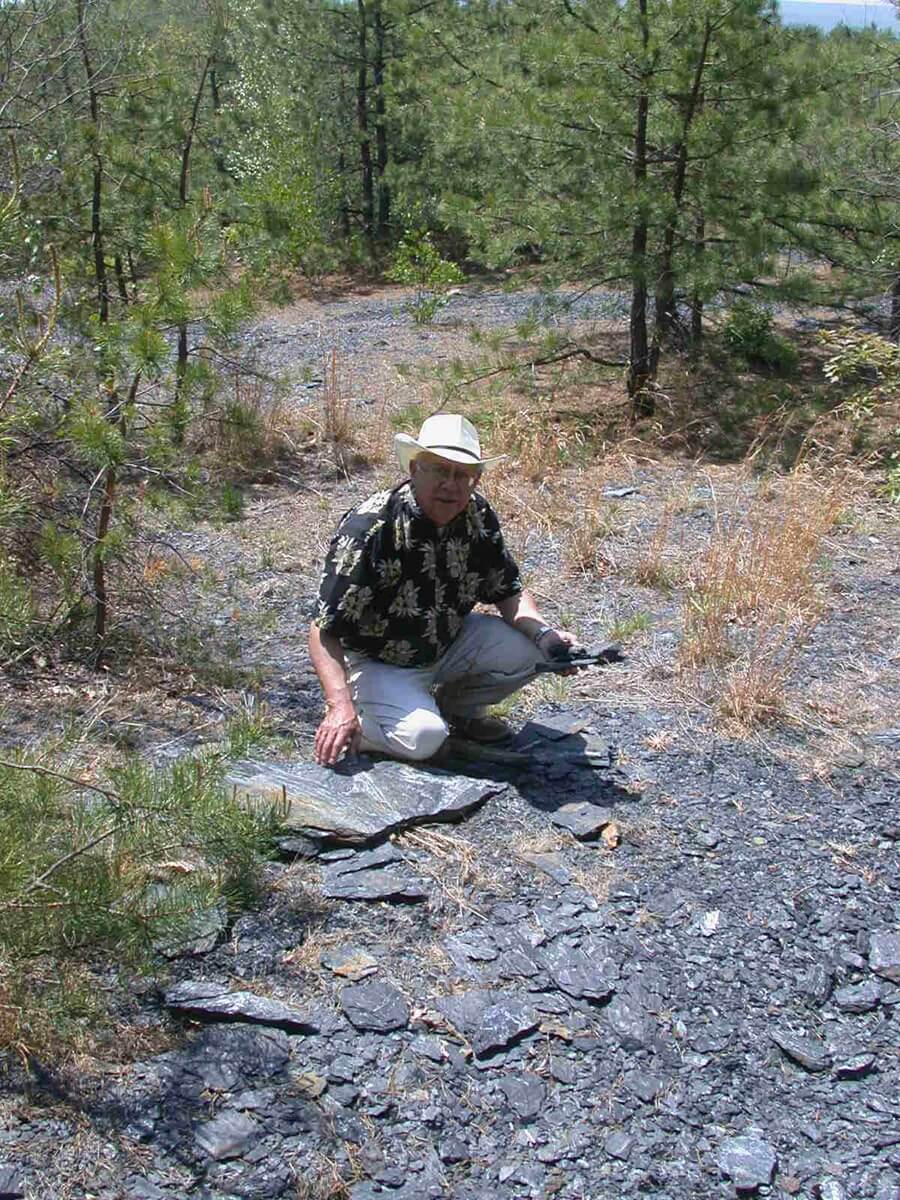

One day, during a visit in 2007, we were driving around town with my husband’s brother, Steve Herman, who sadly passed away 2 years ago. We were on the Burma Road where their old house used to be, now a wasteland left behind by the Reading Anthracite Coal Mining Company, when he asked me if I wanted to visit the fern fossil beds. “Sure”, I said, “let’s go.” “It’s not too far from the road”, he said. “OK”, I said, “no problem, but I am in flip flops, not hiking shoes.” The hike took us about a mile from the road and passed by the shooting range, which made me even more uncomfortable.

My husband collected a few St. Clair fern fossil specimens. Everywhere on the trail, up and down the hill, fern fossils covered the ground.

When we reached the fossil beds, I truly wasn’t prepared to the sheer numbers of the fern fossils lying there. Everywhere on the trail, up and down the hill, fern fossils covered the ground. We had no bags or buckets, as this was not a pre-arranged rockhounding trip, so we used our hats and T-shirts to carry out as many fossils as we possibly could. And since we had already moved to Arizona, we had to ship our treasures back home.

Most St. Clair fern fossils occur on black shale matrix, and show a characteristic white coating of the mineral pyrophyllite. On some occasions, there is a yellow coating.

Andy and his brother, Steve Herman, examine the fern fossils

A few years earlier, we were participating at the Macungie Gem & Mineral show, hosted by the Pennsylvania Earth Sciences Association, and one of the dealers, a fossil collector and teacher at a local school, had a nice selection of the St. Clair fern fossils. He had a few large specimens on which white arrows pointed to and identified each type of fossil, because he used to take them to schools for presentations. I wanted Andy to have some good specimens of his hometown fossils, so after a brief negotiation, those beautiful specimens came back with us. They are still part of our collection. The largest one is 2 feet, 5 inches across and 17 inches tall, with visible fossils on the both sides.

One of the most commonly found fern in the fossils from St. Clair is Pecopteris, an extinct genus of seed fern.

All these plant fossils occur in the Llewellyn Formation. The plants died and fell into the swamp, and because of the environment’s low temperature, pressure and oxygen conditions, the plant tissue was slowly replaced by pyrite from sulfides. It is believed that the whitish mineral coating, an aluminum silicate called pyrophyllite, replaced the pyrite at a later stage, as the sediments piled up and the temperature and pressure became greater. In some instances, there is a yellow coating. The black shale matrix can easily be split, which may reveal fossils of better quality or different types that were hiding inside.

Another fern most commonly found in the fossils from St. Clair belongs to the extinct genus of Alethopteris.

A fern is one of a group of vascular plants that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. Ferns first appeared in the fossil record about 360 million years ago (mya), and those from St. Clair date from around 300 mya.

The ferns most commonly found in the fossils from St. Clair are of the extinct genus of Alethopteris, the seed ferns Pecopteris and Neuropteris (and Neuropteris Ovata), and Sphenophyllum, with fossilized leaf whorls, which are arrangements of sepals, petals, leaves, stipules or branches that radiate from a single point (Common Fossils of Pennsylvania, Donald M. Hoskins, 1973, 1999, 2019). Also found are Cordaites, an extinct genus of leaf seed plants with long strap-like leaves with nearly parallel edges (318 to 299 mya).

All St. Clair fossil bed sites are owned by the Reading Anthracite Coal Company, and have now been fenced off. Any digging or surface collecting is strictly prohibited. Some local gem and mineral clubs have received permission to go in and collect. Please check with your local club. Also, please respect the privacy rules and keep safety in mind.

Two Pennsylvania museums have great fossil collections: the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, in Pittsburgh, and the State Museum of Pennsylvania, in Harrisburg. The Rutgers Geology Museum in New Brunswick, New Jersey, also has a fern fossil collection.

This article, with personal recollections, is a tribute to my husband’s hometown of St. Clair and his memories, heritage and family.

Helen Serras-Herman, a 2003 National Lapidary Hall of Fame inductee, is an acclaimed gem sculptor with over 39 years of experience in unique gem sculpture and jewelry art. See her work at www.gemartcenter.com and her business Facebook page at Gem Art Center/Helen Serras-Herman

All photos by Helen Serras-Herman

The Cover photo is a large specimen in our collection of St. Clair fern fossils measures 10 inches wide by 15 inches tall, and features Pecopteris, Neuropteris ovate, and Cordaites with long, strap-like leaves.