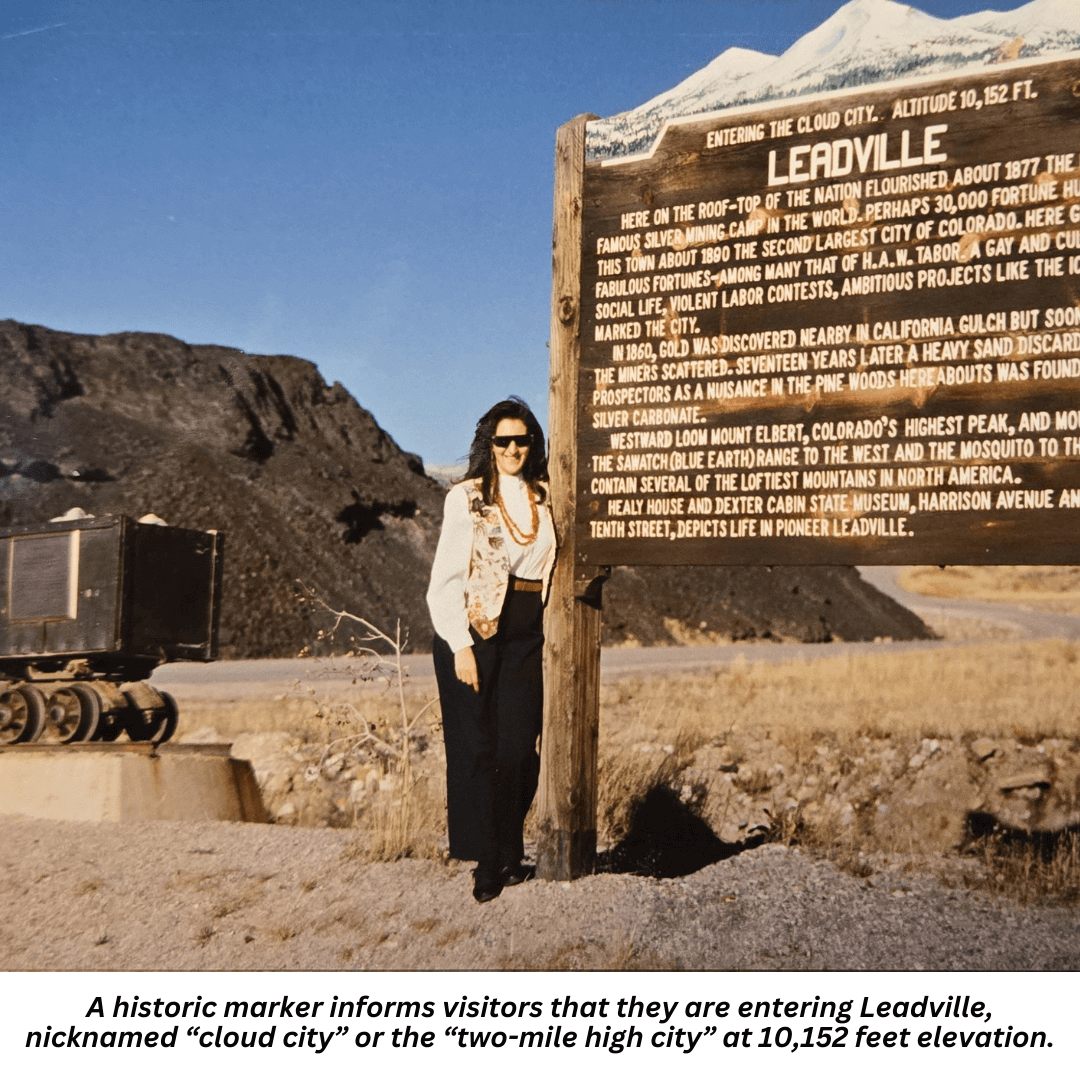

Leadville is a late-1800s mining town, reached in under a two-hour drive west from Denver on I-70. The riches from the mines built the city, home to 30,000 residents at its peak. Beautiful Victorian buildings, museums, and the Tabor Opera House fill Leadville’s downtown Historic District, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966. Sixty-seven mines are part of this district. Leadville is “the highest city in the United States,” situated at 10,152 feet elevation. A historic marker informs visitors that they are entering Leadville, nicknamed “cloud city” or the “two-mile high city.

When we visited Denver during the September shows, the Rocky Mountains – Mount Elbert (Colorado’s highest peak) and Mount Massive surrounding Leadville were always snow-capped, providing awe-inspiring scenery.

Gold and Silver Discoveries in Leadville

Placer gold was first discovered in 1859 in California Gulch, later becoming Oro City (a ghost town today). But by 1866, nearly all placer gold was depleted, and most of the 6,000 miners left. Horace A. W. Tabor, a stone cutter from New England later known as “Leadville’s Silver King,” first came West with his wife Augusta with the gold rush of ’59. They arrived in Oro City in 1868, and Tabor was appointed postmaster.

In 1877, the heavy black sand that was causing problems for placer gold sluice boxes was assayed to be 40% lead (the mineral cerussite), with a high content of 15 ounces of silver per ton. This kick-started one of the most famous silver mining camps in Leadville, three miles away from Oro City.

Tabor moved his operations to this new camp in 1877, which he named Leadville, and within six months, he was chosen mayor. Hotels, restaurants, saloons, and brothels sprung up around Leadville. Tabor grubstaked two German prospectors, August Rische, and George Hook, for a third interest in any mine they found. Their claim on Fryer Hill was the Little Pittsburgh. Within a few months, the three partners had a bonanza income of $50,000 a month. Soon after, the other two partners sold their interests, but Tabor kept his. He became Leadville’s first postmaster and opened the first bank, Tabor Hose Co, and the Tabor Opera House in November 1879.

But Tabor’s marriage to his austere New Englander wife Augusta was crumbling as she disapproved of his parties and excessive spending.

The Story of Baby Doe

Elizabeth Doe Tabor, born Elizabeth McCourt, was first married to Harvey Doe in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. They moved to Colorado, worked at the mines, and dreamed of riches, but her marriage fell apart, too. She became famous around the mines for her beauty and was nicknamed “Baby Doe.” After she met Horace Tabor in 1880, while he was still married, they began a relationship that would be frowned on for the rest of their lives.

After Tabor’s divorce, Baby Doe married Tabor in March 1883 in Washington D.C., as Tabor was briefly a U.S. Senator. Even President Arthur attended the lavish wedding. She was really in love with Tabor, a man twenty-four years her senior (Silver Queen, Caroline Bancroft, 1955, 1992). Her wedding dress was a marabou-trimmed, heavily brocaded white silk damask dress at a legendary cost of $7,000. The dress is now at Denver’s History Colorado. Baby Doe was supposed to wear Tabor’s present, a $90,000 diamond necklace, which was sold to him as part of Queen Isabella’s jewels, but instead wore a lariat of pearls, believing them also to be Isabella’s, a complete myth (Silver Dollar, David Karsner, 1932, 1944).

For a decade, the Tabors lived an opulent life, spending money recklessly and making unpromising investments. Tabor’s great fortune is estimated at around $11,000,000 at the time of their marriage. Tabor purchased the Matchless Mine, which was close to the Little Pittsburgh, for $117,000, which was then paying him $80,000 a month.

The Tabors had their first daughter, Lillie, in 1884, and after the loss of a baby boy, another daughter in 1889, named Silver. The Denver society women never called on her, making Baby Doe Tabor socially isolated and unhappy.

Horace refused to notice the economic storm warnings and the spiraling-down price of silver in the early 1890s until the demonetization of silver was established by the stroke of President Cleveland’s pen in 1893. The Silver Panic devalued their fortunes and made the silver mines worthless, especially the Matchless Mine. Within two years, they had mortgaged all properties, everything was foreclosed, and they went bankrupt. Tabor became a day laborer, and Baby Doe did manual hard work until he was appointed postmaster in Denver. They lived there only fifteen months until Tabor suddenly passed away from appendicitis in 1899.

As the legend goes, his dying words to Baby Doe were, “Hang on to the Matchless. It will make millions again.” And she did for nearly 36 years after Tabor’s death. Baby Doe spent the rest of her life in increasing poverty, personal tragedy, and growing obscurity (The Legend of Baby Doe, John Burke, 1974, 1989). The Matchless Mine survived bad management, mortgages, and foreclosures. From being the “Silver Queen of Colorado,” the heartbroken widow Baby Doe Tabor lived in a small tool cabin behind the shaft and the hoist house, penniless and alone, until she was found frozen on March 7, 1935.

Leadville Today

The town is filled with museums, all within a short walking distance, showcasing pioneer and mining life. At the Heritage Museum, among other artifacts, there is a scale model of the Leadville Ice Palace, which operated only for a few months in 1896. The National Mining Hall of Fame & Museum is a must-stop for every mineral enthusiast, housed in Leadville’s 1899 original high school. Founded in 1987, the museum has over 1,000 minerals, crystals, and gems from around the world, dinosaur footprints, meteorites, underground mine replicas, hand-carved dioramas depicting the 1800s Colorado Clear Creek gold rush, murals, paintings, and historical maps that share the story of mining and metal exploration. The museum is located at 120 West Ninth Street.

Visitors can take the Mineral Belt Trail (www.mineralbelttrail.com ) to explore parts of the mining district. The Route of the Silver Kings (www.routeofthesilverkings.org) is a mapped route with 14 stops and 20 significant historical locations that provide a self-guided tour of the entire district.

Touring the Matchless Mine

Visitors can take a surface tour of the historic Matchless Mine and learn about Tabor’s legendary story. You can peer (not enter) into the shaft of one of the wealthiest mines of Colorado’s Silver Rush and tour Baby Doe Tabor’s restored cabin, hoist House, blacksmith shop, and headframe. The site is open annually from Memorial Day to late September; guided tours are held daily at 10:00 am and 12:00 pm. It is located 1.2 miles east of Leadville on East 7th Street. The site is part of the National Mining Hall of Fame & Museum. Visit www.MiningHallofFame.org for museum and site hours and reservations.

The Tabor Opera House

Visitors can take self-guided or guided tours at the Tabor Opera House, located at 308 Harrison Avenue, in the heart of historic Leadville. It is a massive three-story building made of stone, brick, and iron, trimmed with Portland cement, built in 1879 in just 100 days. Visit www.taboroperahouse.org

The Silver Dollar Saloon & Leadville Mural

You can’t miss the Silver Dollar Saloon at 315 Harrison Avenue, originally opened in 1879. Here, outlaw John Henry “Doc” Holiday shot policeman Billy Allen in 1884. An imposing antique bar and the original tile floor remain today.

Around the corner from the Silver Dollar Saloon is the beautiful Leadville Mural, painted on the side of the Leadville Chronicle by artist F.F. Haberlein. It is acrylic paint on brick.

Helen Serras-Herman, a 2003 National Lapidary Hall of Fame inductee, is an acclaimed gem sculptor and FGA graduate gemologist with over 40 years of experience in unique gem sculpture and jewelry art. See her work at www.gemartcenter.com and her business Facebook page at Gem Art Center/Helen Serras-Herman.

All photos by Helen Serras-Herman and Andrew Herman, unless otherwise cited.